When the UK Supreme Court ruled on 1 August 2025 at 4:35pm UTC, it didn’t just settle a legal dispute—it shattered the expectations of millions of UK drivers who thought they were owed money. The Court overturned a 2024 Court of Appeal decision that had found car dealers acted unlawfully by hiding commission payouts from customers. Now, instead of automatic refunds, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is scrambling to design a compensation scheme that may leave most people with less than £950—or even just £700—per finance deal. The twist? The very lenders who profited from opaque deals—Close Brothers and MotoNovo Finance—won the case. And now, the Treasury says it’s time to fix the system, not punish the lenders.

How the Commission Scandal Worked

Between 2007 and January 2021, car dealers acted as brokers for finance agreements. They didn’t just sell you a car—they also arranged your loan. And here’s the catch: the higher the interest rate you agreed to, the more commission the dealer earned. This system, called discretionary commission arrangements (DCAs), meant a dealer could earn £1,500 extra by pushing a 7% loan instead of a 5% one—without telling you. The FCA banned DCAs in 2021 after years of complaints, but the damage was done. An estimated 23 million UK drivers took out car finance during that period. Consumer Voice’s survey found 75% said they’d have shopped around differently if they’d known dealers made money off their interest rate. Sixty-five percent trusted their dealer implicitly. That trust is now in tatters.The Legal Rollercoaster

The case started with three individuals: Mr. Johnson, Mr. Wrench, and Mrs. Hopcraft. All bought used cars between 2015 and 2019. Each was presented with just one finance option. Only later did they learn the dealer earned thousands in commission from the lender. In October 2024, the Court of Appeal ruled unanimously that this was a breach of fiduciary duty. “Burying such a statement in the small print which the lender knows the borrower is highly unlikely to read will not suffice,” wrote Lady Justice Andrews, joined by Lords Birss and Edis. It felt like justice. But on 1 August 2025, the UK Supreme Court reversed that. The judges didn’t say the practice was fair—they said the law didn’t clearly require dealers to disclose commissions at the time. The ruling wasn’t about morality. It was about legal precedent. And it left consumers in legal limbo.The FCA’s Compromise

Within hours of the verdict, the FCA announced a consultation on a voluntary redress scheme—set to launch in October 2025. The numbers are staggering: total payouts could range from £9 billion to £18 billion. But here’s the kicker: most claimants will receive less than £950 per agreement, according to FCA estimates. Carwow’s analysis, citing lender projections, suggests the average payout might settle at £700. That’s roughly what you’d get for a new set of tyres and an oil change. Close Brothers and MotoNovo Finance are expected to pay around £8.2 billion combined. The first cheques won’t arrive until 2026. The FCA is still deciding who qualifies. Will it cover everyone who signed a finance deal between 2007 and 2024? Or only those who can prove they were misled? What about people who refinanced? The rules are still being drafted. And critics say the delay is a gift to lenders.What the Treasury Really Means

The Treasury’s statement sounded measured: “We respect this judgment... we are taking forward significant changes to the Financial Ombudsman Service and the Consumer Credit Act.” But behind the scenes, insiders say ministers are terrified of a flood of lawsuits. Consumer Voice warned Chancellor Reeves might push retroactive legislation to shield lenders. Instead, the government chose reform over restitution. The goal? Make future lending clearer—not fix the past. That’s cold comfort to someone who paid £12,000 extra in interest because their dealer got a £2,000 kickback. It’s cold comfort to the 65% who trusted their dealer—and got burned.What’s Next?

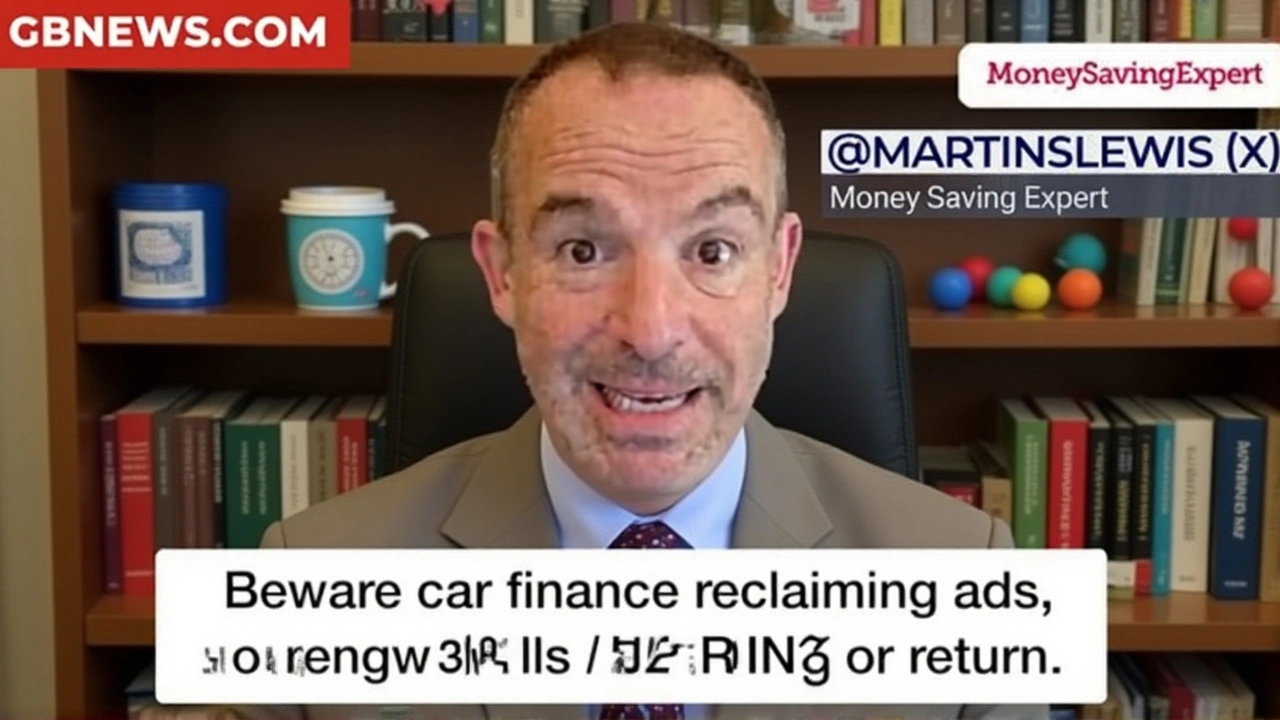

October 2025 is the deadline for FCA feedback. By early 2026, the scheme’s rules will be finalised. Lenders will start paying. But here’s the real question: will anyone bother to claim? Many won’t know they’re eligible. Others won’t bother with paperwork for £700. And some—especially older drivers who bought cars on credit decades ago—may have passed away before seeing a penny. Meanwhile, the FCA is quietly reviewing whether to ban other hidden fees in auto finance. Brokers are being told to document every conversation. Dealers are being forced to use plain-language disclosures. But for those already caught in the DCA trap? The clock is ticking. And the money? It’s not coming fast.Why This Matters Beyond Cars

This isn’t just about car loans. It’s about how regulators respond when the system works too well—for the powerful. The Supreme Court didn’t say the practice was ethical. It said the law was silent. That’s a dangerous precedent. If lenders can profit from obscurity, and courts won’t force transparency retroactively, what’s stopping banks from doing the same with mortgages? Or insurers with hidden policy fees? The real scandal isn’t the commission. It’s that we waited until 2021 to ban it. And now, we’re asking victims to fight for crumbs.Frequently Asked Questions

Who qualifies for compensation under the FCA’s new scheme?

Anyone who took out a car finance agreement between 2007 and January 2021 through a dealer acting as a broker may qualify. The FCA is still finalising criteria, but early indications suggest claimants must prove they were not informed about discretionary commission arrangements. Those who financed cars with only one offered rate, or where the dealer received higher commissions based on interest rate hikes, are most likely eligible. Claims will require loan documentation and proof of purchase date.

Why did the Supreme Court side with the lenders?

The Court ruled that while the practice was ethically questionable, the law at the time—before the 2021 FCA ban—did not explicitly require dealers to disclose commission structures. The Court of Appeal had found a breach of fiduciary duty, but the Supreme Court determined that duty wasn’t legally established under consumer credit law as it stood between 2007 and 2021. It was a legal technicality, not an endorsement of the practice.

How much money will most people actually receive?

The FCA estimates most individuals will receive under £950 per agreement, with Carwow’s analysis suggesting an average payout of £700. Total compensation could reach £8.2 billion, primarily paid by Close Brothers and MotoNovo Finance. The amount depends on the loan size, interest rate differential, and whether the consumer can prove they were unaware of commission incentives. Many smaller loans may yield payouts under £300.

When will compensation payments start?

The FCA’s consultation runs until October 2025, after which final rules will be published. Lenders have until early 2026 to set up claims systems, meaning the first payments won’t reach consumers until late 2026. The process is expected to take 18–24 months to complete for all eligible claimants. Those who don’t file within two years of the scheme’s launch may lose their right to claim.

Are dealers personally liable for these payouts?

No. The responsibility falls on the finance lenders—primarily Close Brothers, MotoNovo Finance, and other major lenders who used discretionary commission arrangements. While dealers facilitated the deals, the legal liability rests with the lenders who paid the commissions. Dealers may face reputational damage, but they won’t be paying out of pocket unless they acted fraudulently beyond the DCA structure.

Will this affect future car buying?

Yes. Since the 2021 ban on DCAs, dealers must now offer fixed commission rates and disclose all finance options transparently. The FCA is tightening rules on broker-lender relationships, requiring written consent for interest rate adjustments and mandating clear comparisons of finance deals. Buyers should now receive at least three financing options with commission details—something most didn’t get before 2021. This ruling reinforces the need for vigilance, even in a reformed system.